When building microservices architectures, one of the trickiest puzzles is figuring out how these independent services talk to each other. This article is your practical, no-BS architectural guide to microservices communication. We’re not here just to throw definitions at you; instead, we dive into real design decisions, trade-offs, and patterns that shape service-to-service interactions.

In plain terms, microservices communication or inter-service communication means the ways different microservices send data, commands, or events between each other to work together as a system. How you choose to connect them affects everything from latency to how tightly they’re coupled, as well as your system’s scalability and fault tolerance.

This guide targets software architects, senior developers, and technical leads who are making the calls on designing these communication flows—especially the tricky parts where practical realities challenge theory.

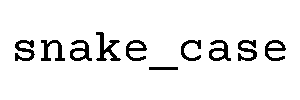

You’ll find clear distinctions between synchronous communication, where a calling service waits for an immediate response, and asynchronous communication, where it sends a message and moves on. The choice between these fundamentally shapes your latency, coupling, scalability, and reliability.

To keep things grounded, we use a consistent e-commerce domain as our running example: think services like Orders, Payments, and Notifications. This lets us ground abstract patterns in concrete, relatable scenarios.

Ready to explore the rich world of microservices communication and make confident architectural choices? Let’s dive in.

Core Concepts of Microservices Communication

Moving from a monolith to microservices might feel like switching from passing notes in class to trying to send messages across an overcrowded hallway. Communication in distributed systems is fundamentally harder because the reliable, shared memory of a monolith is replaced by networking, which can be flaky, slow, or partially broken.

Imagine:

- Phone call: You call a colleague and expect an immediate answer—this is synchronous communication.

- Email: You shoot a message and don’t expect an instant response—this is asynchronous communication.

- Group notification: You send a broadcast like a group text, and many people hear it, reacting independently—this is pub/sub event-driven communication.

Formally, synchronous means the caller waits (blocks) until the callee replies. Asynchronous means the caller sends a message (or event) and moves on, often without knowing immediately if the processing succeeded.

Key terms we’ll use:

- Request/Response: typical pattern where a client sends a request, the server replies.

- Messages: discrete packets of data, often commands or events sent via brokers.

- Events: facts or notifications something happened, used in event-driven architecture.

- Service-to-service communication: how services directly exchange data.

- Event-driven architecture: a design where state changes or actions propagate as events.

Our e-commerce example involves several services:

- User Service: manages user info and authentication.

- Catalog Service: handles product listings.

- Orders Service: processes orders.

- Payments Service: authorizes and captures payments.

- Notifications Service: sends emails or SMS.

Throughout this article, we’ll refer to related terms like inter-service communication in our distributed system, and how event-driven architecture helps decouple processing.

Synchronous vs Asynchronous Communication at a Glance

| Aspect | Synchronous | Asynchronous |

|---|---|---|

| Caller Behavior | Waits for immediate response | Sends message, continues without waiting |

| Typical Technologies | HTTP/REST, gRPC, GraphQL Gateways | Message Brokers (Kafka, RabbitMQ), Pub/Sub, Async APIs |

| Latency | Lower (perceived), blocking | Higher (initial), non-blocking |

| Coupling | Tight (runtime dependency) | Loose (time decoupled) |

| Complexity | Lower to start, can grow due to cascades | Higher operational and design complexity |

| Scalability | Limited by sync bottlenecks | Better spike handling and horizontal scale |

| Reliability | Fragile to downstream failures | More resilient, better failure isolation |

Simply put, synchronous communication is like calling someone and waiting, whereas asynchronous is more like sending a message in a bottle and hoping it reaches land sometimes soon. Each has its place.

Synchronous Microservices Communication Patterns

Synchronous inter-service communication shines when user-facing flows demand immediate results, such as during checkout or login, and when strict latency SLAs apply. It also works great for read-heavy queries where live data is a must.

This section focuses on patterns using HTTP/REST and gRPC (with a nod to GraphQL) for direct service-to-service calls.

REST over HTTP for Service-to-Service Communication

REST (Representational State Transfer) is the bread and butter of microservices communication. It uses resource-focused URLs, standard HTTP methods like GET, POST, PUT, DELETE, and JSON for data serialization. It’s often the easiest default choice for internal service calls.

For example, during checkout in our e-commerce domain, the Order Service might synchronously call the Payment Service‘s POST /payments endpoint to authorize the credit card before finalizing the order.

// PaymentController.cs - Payment Service API endpoint for payment authorization

using Microsoft.AspNetCore.Mvc;

[ApiController]

[Route("payments")]

public class PaymentController : ControllerBase

{

[HttpPost]

public IActionResult AuthorizePayment([FromBody] PaymentRequest request)

{

// Simplified payment authorization logic

bool authorized = PaymentProcessor.Authorize(request.CardNumber, request.Amount);

if (authorized)

return Ok(new { Status = "Authorized" });

else

return BadRequest(new { Status = "Declined" });

}

}

// Order Service - Synchronous call to Payment Service using HttpClient

var httpClient = new HttpClient();

var paymentRequest = new PaymentRequest { CardNumber = "...", Amount = 99.99M };

var response = await httpClient.PostAsJsonAsync("https://paymentservice/payments", paymentRequest);

if(response.IsSuccessStatusCode)

{

var result = await response.Content.ReadFromJsonAsync();

// Proceed with order confirmation

}

else

{

// Handle payment failure

}

Pros:

- Simplicity and familiarity

- Abundant tooling and libraries

- Debuggable, human-readable JSON payloads

- Firewall and proxy friendly

Cons:

- Higher overhead compared to gRPC

- Potential for tight runtime coupling

- Cascading failures if downstream services slow or fail

Use REST when…

- Teams need quick setup and debug-friendly communication.

- Service boundaries involve coarse-grained APIs with stable contracts.

- Human readability in the wire format is beneficial.

Avoid REST if…

- Ultra-low latency high-volume calls are critical.

- You need strong, binary contract enforcement.

- Services are chatty and calls create complex chains.

Rest is often the common default choice for microservices communication, especially for initial service integrations.

gRPC for High-Performance Service-to-Service Calls

gRPC, paired with Protocol Buffers (Protobuf), is the turbocharged cousin to REST. It offers efficient binary serialization, strongly typed contracts, and HTTP/2 multiplexing. Plus, it supports bidirectional streaming for rich communication.

For example, the Catalog Service might call the Inventory Service via gRPC to fetch stock levels for many SKUs in a single, high-performance request.

// inventory.proto - Protocol Buffer definition for Inventory Service

syntax = "proto3";

service InventoryService {

rpc GetStockLevels (StockRequest) returns (StockResponse);

}

message StockRequest {

repeated string sku_ids = 1;

}

message StockResponse {

map<string, int32> stock_levels = 1;

}

// C# client code - Calling Inventory Service via gRPC

var client = new InventoryService.InventoryServiceClient(channel);

var response = await client.GetStockLevelsAsync(new StockRequest { SkuIds = { "SKU123", "SKU456" } });

foreach (var stock in response.StockLevels)

{

Console.WriteLine($"Item: {stock.Key}, Quantity: {stock.Value}");

}

Trade-offs vs REST:

- Significantly better performance and type safety

- More complex toolchain and debugging is less straightforward

- Binary payloads are less firewall-friendly

Use gRPC when…

- Performance and low latency matter.

- Strongly typed, contract-first APIs are preferred.

- Teams have expertise with gRPC and Protobuf tooling.

Avoid gRPC if…

- Debuggability from browsers or cURL is a priority.

- Client compatibility across many languages or platforms is limited.

GraphQL API Gateways for Aggregated Queries

GraphQL typically lives at the edge, acting as an API gateway. Instead of direct service-to-service use, it aggregates data from multiple microservices, simplifying frontend interactions.

E-commerce example: fetching a user’s full order history with payment and shipping details in one GraphQL query. Internally, the GraphQL server fans out calls to Orders, Payments, and Shipping services using REST or gRPC.

Benefits:

- Clients request exactly what they need, avoiding over-fetching.

- Simpler interface for frontend teams.

Costs:

- Complex gateway logic

- N+1 problem with multiple downstream calls

- Complex caching strategies required

Here’s a simplified pseudocode snippet that resolves a GraphQL field by calling downstream microservices:

// GraphQL resolver - Aggregating data from multiple microservices

resolveOrderHistory = async (userId) => {

var orders = await ordersService.getOrders(userId);

var payments = await paymentsService.getPayments(orders.map(o => o.id));

var shipping = await shippingService.getShipping(orders.map(o => o.id));

return orders.map(order => ({

...order,

payment: payments.find(p => p.orderId == order.id),

shipping: shipping.find(s => s.orderId == order.id),

}));

};

Decision Guide: When to Use Synchronous Communication

- Use synchronous communication when a user request requires an immediate, consistent response (checkout, login, product details).

- Avoid long synchronous chains spanning more than 2–3 services to reduce latency spikes and cascade failures.

- If a user is waiting on the response, prefer synchronous communication.

- If workloads are background or can tolerate delays, favor asynchronous patterns.

- For composing multiple data reads, use an API gateway or GraphQL combined with internal synchronous calls.

In summary:

Is the user waiting? Synchronous. Can it wait? Asynchronous.

Asynchronous Microservices Communication Patterns

Asynchronous microservices communication relies on messages and events flowing through brokers like Kafka, RabbitMQ, Azure Service Bus, or AWS SNS/SQS. This approach offers loose coupling, resilience to traffic spikes, and better failure isolation.

Message-Driven Communication (Queues)

Queues implement point-to-point messaging: one producer sends a message to a queue, and a single consumer processes it. This pattern is excellent for commands or tasks requiring ordered, reliable delivery without tying up the caller.

Example: The Order Service publishes a ChargePayment command to a queue, which the Payment Service consumes asynchronously.

// Producer (Order Service) - Sending a message to RabbitMQ queue

var factory = new ConnectionFactory() { HostName = "rabbitmq" };

using var connection = factory.CreateConnection();

using var channel = connection.CreateModel();

string queueName = "ChargePaymentQueue";

channel.QueueDeclare(queue: queueName, durable: true, exclusive: false, autoDelete: false, arguments: null);

var messageBody = JsonSerializer.SerializeToUtf8Bytes(new { OrderId = 123, Amount = 99.99M, CardNumber = "****" });

var properties = channel.CreateBasicProperties();

properties.Persistent = true;

channel.BasicPublish(exchange: "", routingKey: queueName, basicProperties: properties, body: messageBody);

// Consumer (Payment Service) - Processing messages from RabbitMQ queue

channel.BasicConsume(queue: queueName, autoAck: false, consumer: new EventingBasicConsumer(channel)

{

Received = (model, ea) =>

{

var body = ea.Body.ToArray();

var paymentCommand = JsonSerializer.Deserialize(body);

// Process payment logic

channel.BasicAck(deliveryTag: ea.DeliveryTag, multiple: false);

}

});

Pros:

- Buffers requests and handles back-pressure

- Decouples producer and consumer in time

- Improves isolation to failures

Cons:

- Increased complexity and eventual consistency

- Requires managing additional broker infrastructure

Use queues when…

- Operations are long-running or can be delayed (e.g., payment processing, email sending).

- You want to decouple services and absorb load spikes.

Avoid queues if…

- Strong immediate consistency is mandatory in user flows.

- Low latency, request-response style is required.

Publish/Subscribe Events and Event-Driven Architecture

Pub/sub enables one service (producer) to publish events to a topic, which many services (subscribers) can listen to and react independently. This is a staple of event-driven architecture.

Example: The Order Service publishes an OrderPlaced event. Multiple services consume it: Notifications sends email, Analytics updates metrics, Fraud Detection runs checks.

C# pseudo-code for publishing and subscribing:

// Producer (Order Service) - Publishing event to Kafka topic

var producer = new ProducerBuilder<string, string>(config).Build();

await producer.ProduceAsync("order_events", new Message<string, string> { Key = order.Id.ToString(), Value = JsonSerializer.Serialize(orderPlacedEvent) });

// Consumer (Notification Service) - Subscribing to Kafka topic

var consumer = new ConsumerBuilder<string, string>(config).Build();

consumer.Subscribe("order_events");

while(true)

{

var consumeResult = consumer.Consume();

var orderEvent = JsonSerializer.Deserialize(consumeResult.Message.Value);

SendEmailNotification(orderEvent);

}

Semantic note: Commands express intent (“do this”), while events communicate facts (“this happened”). This distinction is fundamental in microservices communication to clarify responsibilities and reactions.

Event Sourcing and CQRS in Microservices

Event Sourcing means persisting all state changes as an immutable event log. CQRS (Command Query Responsibility Segregation) splits write and read models for optimization.

In our e-commerce example, the Orders Service stores each step—order created, payment authorized, shipped—as events. A projection then builds a read-optimized view used by queries.

These advanced patterns help with complex business rules, auditability, and temporal queries but come at the price of additional operational overhead and learning curve.

Use them selectively when your domain complexity justifies their cost, never by default.

Serialization Formats: JSON vs Protobuf vs Avro

| Format | Size | Speed | Human-Readable? | Schema Evolution | Language Support |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JSON | Large | Slower | Yes | Basic (manual) | Universal |

| Protobuf | Compact | Fast | No | Good (versioning support) | Multi-language |

| Avro | Compact | Fast | No | Excellent (schema registry) | Broad |

Recommendations:

- Internal gRPC calls: use Protobuf.

- Public or edge APIs: stick with JSON for compatibility.

- High-throughput Kafka event streams: choose Protobuf or Avro for compactness and schema evolution.

Decision Guide: When to Use Asynchronous Messaging

- Use async messaging for long-running jobs (fraud checks, email notifications), fan-out events, and cross-cutting concerns like analytics.

- Decouple teams and release cycles where independent deployment is critical.

- Decision tree:

- Can the operation be delayed? → Yes: Async.

- Are multiple services interested in a domain event? → Yes: Pub/Sub.

- Is ordering or exactly-once delivery important? → Use partitioning, idempotency, outbox pattern.

Choosing the Right Microservices Communication Pattern

This is the heart of your architectural challenge. How do you pick the right pattern given your constraints and requirements? This section guides architects to balance trade-offs and pick their communication approaches thoughtfully.

Trade-off Matrix: Latency, Reliability, Coupling, Complexity, Scalability

| Pattern | Latency | Reliability | Coupling | Complexity | Scalability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| REST | Medium | Medium | High | Low | Medium |

| gRPC | Low | Medium | Medium | Medium | High |

| Queue Messaging | High | High | Low | High | High |

| Pub/Sub Events | High | High | Low | High | High |

| Event Sourcing / CQRS | Variable | High | Low | Very High | High |

Use this matrix as a tool to compare patterns across critical axes. For example, if ultra-low latency is mandatory, gRPC may be your friend, while Kafka’s pub/sub excels when decoupling and scalability are priorities over immediate consistency.

Practical Decision Framework for Architects

- Identify flows that are user-facing vs back-end batch or integration jobs.

- Determine consistency needs: strong (sync) or eventual (async).

- Assess latency SLAs: milliseconds or seconds tolerated.

- Analyze team skills and maturity with brokers, orchestration, and service meshes.

- Define default communication patterns and allowed exceptions per scenario.

Generally:

- User-facing with strong consistency: synchronous REST or gRPC.

- Background jobs, notifications: asynchronous messaging.

- Complex transactional flows: sagas with orchestration or choreography.

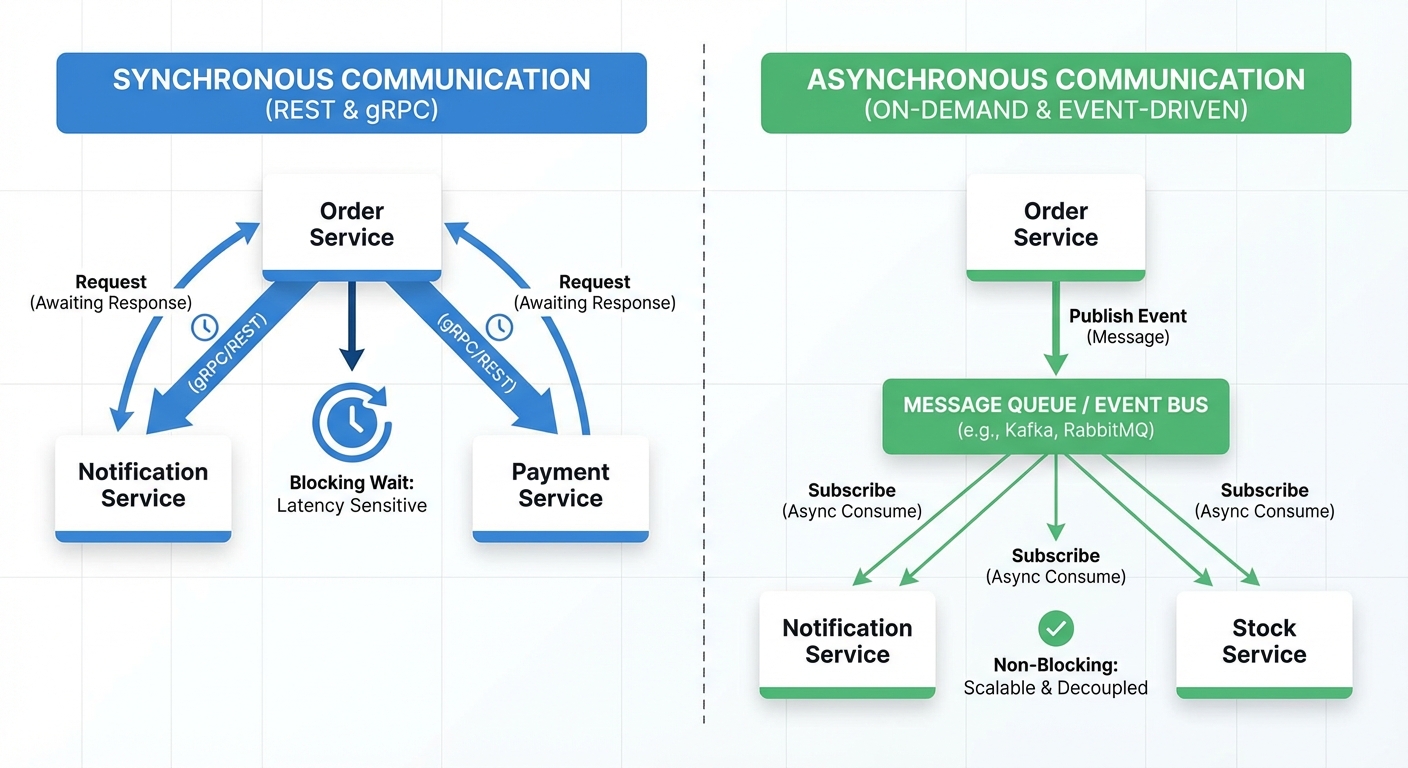

Example: Designing Communication for an E-commerce Checkout Flow

Imagine a user checking out items in their cart:

- The Order Service synchronously calls Payment Service (REST/gRPC) to authorize the payment.

- If successful, it synchronously fetches catalog pricing and discount data for validation.

- After order confirmation, asynchronous messages are sent to Notifications Service to email the user, Analytics Service to update sales metrics, and Shipping Service to initiate delivery.

Sequence diagram (text):

User → Order Service: Checkout Request Order Service → Payment Service: Authorize Payment (sync) Payment Service → Order Service: Authorization Response Order Service → Catalog Service: Validate Pricing (sync) Order Service → Notifications Service: Send Confirmation Email (async) Order Service → Analytics Service: Record Sale (async) Order Service → Shipping Service: Create Shipment (async)

This mixed approach balances immediate consistency for payment with eventual consistency for side effects, optimizing user experience and system resilience.

Reliability, Resilience, and Failure Handling in Microservices Communication

In distributed systems, failures are a fact of life: timeouts, slow responses, broker outages, and network partitions happen all the time. Handling these gracefully is non-negotiable.

Timeouts, Retries, and Exponential Backoff

Every remote call must have timeouts to avoid waiting forever. Retries with exponential backoff and jitter help avoid flooding the system when a downstream is slow or down.

// Resilient HTTP calls using Polly library with retry and exponential backoff

var policy = Policy

.Handle()

.WaitAndRetryAsync(3, retryAttempt => TimeSpan.FromSeconds(Math.Pow(2, retryAttempt)),

(exception, timeSpan, retryCount, context) =>

{

Console.WriteLine($"Retry {retryCount} after {timeSpan} due to {exception.Message}");

});

await policy.ExecuteAsync(async () =>

{

var response = await httpClient.GetAsync("https://paymentservice/payments/123");

response.EnsureSuccessStatusCode();

});

Avoid retries on non-idempotent operations or cap them to prevent side effects.

Circuit Breakers and Bulkheads

The circuit breaker pattern prevents cascading failures by temporarily blocking calls to a failing service. It cycles through states:

- Closed: allow calls.

- Open: block calls.

- Half-open: test if service recovered.

Tools like Polly for .NET or service meshes such as Istio provide built-in circuit breakers and retries at infrastructure level.

Bulkheads isolate resources like thread pools or connection limits per downstream dependency to prevent total system collapse.

Message Delivery Guarantees and Idempotency

Messaging systems offer different delivery guarantees:

- At-most-once: message might be lost.

- At-least-once: message might be duplicated.

- Exactly-once: very hard and costly to guarantee.

Most brokers (Kafka, RabbitMQ) provide at-least-once, so your consumers must be idempotent:

- Use idempotency keys on commands.

- Maintain deduplication tables.

- Check current state before applying changes.

This helps handle duplicates or out-of-order processing gracefully.

Designing for Partial Failures and Network Partitions

Partial failures are the normal state of distributed systems. Design strategies include:

- Fallbacks or degraded modes to return partial results.

- Queueing work locally for retry later.

- Clear error information to clients about failures.

Asynchronous messaging can help absorb partitions but introduces eventual consistency trade-offs.

Data Consistency, Sagas, and Distributed Transactions

Classic distributed transactions (two-phase commit) are mostly abandoned in microservices due to complexity and coupling. Instead, eventual consistency is embraced.

In our e-commerce example, when an order is placed, payment updates may lag, but the system reconciles eventually.

Saga Pattern: Choreography vs Orchestration

Sagas are long-lived transactions broken into steps with compensation logic for failures.

Choreography:

- Order Service publishes

OrderCreatedevent. - Payment Service processes payment, publishes

PaymentSucceededorPaymentFailed. - Shipping Service reacts to

PaymentSucceededand initiates shipment.

Orchestration:

- Central Saga Orchestrator coordinates steps by calling Payment and Shipping services directly.

- Handles compensation actions if steps fail.

Saga sequence diagrams (simplified):

Choreography: Order Service → Event Bus: OrderCreated Payment Service → Event Bus: PaymentSucceeded / PaymentFailed Shipping Service → Event Bus: ShipmentCreated Orchestration: Saga Orchestrator → Payment Service: Process Payment Payment Service → Saga Orchestrator: Success / Failure Saga Orchestrator → Shipping Service: Create Shipment Saga Orchestrator → Compensation if failure

Choreography is loosely coupled but can become hard to trace, while orchestration centralizes control but adds a single point of coordination.

Transactional Messaging and the Outbox Pattern

The outbox pattern ensures reliable messaging by writing state changes and outgoing messages to a single database transaction. A separate process then publishes messages from the outbox.

// Outbox Pattern - Saving Order and OutboxMessage in a single transaction

using var transaction = db.BeginTransaction();

db.Orders.Add(order);

db.OutboxMessages.Add(new OutboxMessage { Payload = Serialize(orderCreatedEvent), Processed = false });

db.SaveChanges();

transaction.Commit();

// Separate background dispatcher reads OutboxMessages, publishes events, marks processed

This avoids message loss or duplication that could occur due to partial failures.

Propagating Data Changes Across Services

Common approaches:

- Event-carried state transfer: send full or partial data within events for consumers to update local caches.

- Event notifications: send event with ID only, forcing consumers to query source services.

Including full order details in an event reduces coupling at runtime but increases event size and schema dependency.

Design this carefully to balance coupling and schema evolution complexity.

Infrastructure Components that Shape Microservices Communication

Communication patterns never live in isolation. API gateways, service registries, load balancers, and service meshes are key enablers that shape how microservices talk.

API Gateways and Edge Communication

API gateways act as the front door to your microservices. They handle authentication, routing, rate limiting, and can aggregate calls to multiple services.

Example: external clients call a single unified /api endpoint, which fans out to Orders, Payments, and other services as needed.

Gateways leave domain logic to microservices, focusing on cross-cutting concerns.

Popular tools include Azure API Management, AWS API Gateway, Kong, and NGINX.

Service Discovery, Load Balancing, and Service Meshes

Service discovery lets services find each other dynamically rather than hardcoding addresses. This can be DNS-based, client-side, or server-side.

Service meshes like Istio, Linkerd, and Consul Connect add sidecar proxies that transparently manage retries, circuit breakers, timeouts, security (mTLS), and observability without application changes.

# Istio VirtualService - Configuring retry and timeout policies

apiVersion: networking.istio.io/v1alpha3

kind: VirtualService

metadata:

name: payment-service

spec:

hosts:

- payment-service

http:

- route:

- destination:

host: payment-service

retries:

attempts: 3

perTryTimeout: 2s

timeout: 10s

Cloud Platform Considerations (AWS, Azure, GCP)

Most cloud providers offer managed services supporting these patterns:

- AWS: API Gateway, ALB/NLB, SQS, SNS, MSK (Kafka), App Mesh.

- Azure: API Management, Service Bus, Event Hubs, AKS with Open Service Mesh or Istio.

- GCP: Cloud Endpoints, Pub/Sub, GKE + Anthos Service Mesh.

While these examples reflect the cloud vendor ecosystem, architectural decisions remain largely cloud-agnostic.

Observability and Monitoring for Microservices Communication

You can’t run reliable microservices communication without top-notch observability: logs, metrics, and distributed tracing are your best friends.

Distributed Tracing with OpenTelemetry, Jaeger, Zipkin

Distributed tracing follows a request across service boundaries using traces and spans. Each remote call creates traces linked by unique identifiers.

// Configuring OpenTelemetry tracing in ASP.NET Core

services.AddOpenTelemetryTracing(builder =>

{

builder

.AddAspNetCoreInstrumentation() // Traces incoming HTTP requests

.AddHttpClientInstrumentation() // Traces outgoing HTTP calls

.AddJaegerExporter(); // Exports traces to Jaeger

});

Passing trace IDs over HTTP headers or message metadata lets you stitch logs and metrics end-to-end.

Logging Correlation IDs Across Services

A correlation ID identifies a single user request as it flows through multiple services. Distinct from trace IDs, these remain constant for business requests.

Pattern:

- Generate correlation ID at API gateway or client edge.

- Pass it through HTTP headers and message metadata.

- Include it in all logs for request cross-referencing.

// Structured logging with correlation ID for distributed tracing

log.LogInformation("Processing order {@OrderId} with CorrelationId {CorrelationId}", orderId, correlationId);

This makes troubleshooting distributed issues far more efficient.

Key Metrics for Communication Paths

- Latency, throughput, error rate, saturation (resource usage)

- Queue length and dead-letter queue size for async messaging

- Set SLIs/SLOs targeting critical flows, like checkout or payment authorization

A dashboard with one panel per dependency gives a quick health overview.

Common Pitfalls in Microservices Communication and How to Avoid Them

Overusing Synchronous Calls and Creating Distributed Monoliths

Many fine-grained synchronous calls create tight runtime coupling—a distributed monolith. This leads to fragile systems, cascading failures, and slowed deployments.

Mitigate by defining coarse-grained APIs, using async events, caching aggressively, and adopting sagas for complex workflows.

Underestimating Operational Complexity of Async Messaging

Message brokers are powerful but can hide failures, poison messages, and broken consumers.

Standardize schemas, apply versioning, configure dead-letter queues, and monitor consumer health closely.

Ignoring Backward Compatibility in Contracts

Breaking changes in APIs or events can wreak havoc in distributed systems.

Adopt versioning strategies, consumer-driven contract testing, and the principle of backward-compatible evolution.

Opinionated Best Practices and Playbook for Microservices Communication

Default Patterns for Common Scenarios

- User-facing reads: REST or gRPC with caching.

- Critical writes (e.g., checkout): synchronous for core logic, asynchronous for side-effects.

- Cross-cutting events (analytics, notifications): pub/sub events.

- Complex long-running business processes: sagas, starting with orchestration.

Checklist for Designing Communication in a New Microservices System

- Define clear domain boundaries and bounded contexts.

- Classify workflows by latency and consistency needs.

- Choose default sync vs async communication mix.

- Decide on serialization formats for each pattern.

- Define and document contracts and versioning.

- Plan observability and resilience patterns from project start.

Encourage teams to codify this checklist in their architecture guidelines to ensure consistency and quality.

FAQ: Practical Questions About Microservices Communication

When Should I Use Synchronous vs Asynchronous Communication?

As a rule of thumb, use synchronous communication when the user is actively waiting for a response and requires strong consistency (e.g., login, checkout). Use asynchronous messaging when operations can be processed later (e.g., sending emails, analytics) or when decoupling release cadence is important.

How Do I Avoid Tight Coupling Between Microservices?

Favor asynchronous events, design coarse-grained APIs aligned with bounded contexts, and evolve schemas backward-compatibly. Avoid chaining many synchronous calls and minimize shared databases.

How Can I Test Microservices Communication Locally?

Use docker-compose setups with service stubs or mocks, employ in-memory message brokers, and adopt contract testing tools to simulate and validate inter-service contracts effectively without full deployments.

Further Reading and References

- Microsoft .NET Microservices Architecture Guide – Communication Chapter

- Building Microservices by Sam Newman

- Microservices Patterns by Chris Richardson

- Apache Kafka Official Documentation

- RabbitMQ Documentation

- Istio Service Mesh Documentation

- OpenTelemetry Specifications and Guides

For deeper dives, explore articles on sagas, event-driven architecture, and service mesh implementations to master the many facets of microservices communication.